1. Empower Yourself

The nutrition world is certainly a moving target, in terms

of the debates that rage on about which of the macronutrients are

healthier as foci for your diet. In my humble opinion, neither the

status quo public health recommendations nor the latest inflammatory

food blogs are reliable enough to slavishly follow. There’s never been a

better time to take the bull by the horns and do your own

research.

Most geeks who are aiming for fitness have some kind of goal in

mind (e.g., getting leaner, building muscle, building a baby). While we

all understand that eating doesn’t require a preparatory biochemical

analysis (in fact, that preoccupation would probably ruin the meal

before the waiter ever brought it—particularly for your dinner

partners), dietary matters do entail the constant launching of complex

chemical reactions in your body, as well as providing the materials for

your own cells over and over again as they are regenerated by the

trillions.

Therefore, understanding some of the basics behind food

constituents can only be empowering. All knowledge without coercion or

propaganda is a form of personal enlightenment.

In fitness terms, by eating, you’re basically rebuilding yourself,

and your level of fitness starts with

nutrition.

2. Macronutrient Ratios

We’ll start by discussing what a macronutrient ratio (MR) is,

because this term comes up a lot in food discussions and provides a

snapshot of the contents of your typical food intake.

Some people want to fine-tune their MRs, for example, in order to

add lean mass (a bit more protein and calories in general), lose some

extra fat (tightly connected to the previous goal), or subtract some

carbs because they’re not doing the “Race Across America” bike race

anymore. The ratio falls into the “good to know” category; check on it

once and you’re good to go, unless you have to radically change your

dietary components.

After discussing MRs, we’ll move on to descriptions of each of the

three macronutrients and what happens during digestion (because the

carbs, fats, and protein that go into your mouth are reformulated—mostly

ripped apart—by the time they hit your bloodstream and body

cells).

2.1 The Ole 30-50-20 Maneuver

When you eat a typical meal or snack, you usually consume

portions of all three macronutrients: carbs, fats, and protein. Unless

you’re nibbling on a stick of butter (100 percent fat by

calories), for example, your breakfast might contain carbs

and maybe a tiny bit of protein (fruit); carbs and some protein

(toast); or fats, protein, and perhaps a few carbs (meat and

eggs).

Note

You generally don’t have to obsess over your

macronutrient ratio if you aim for a variety of real food: veggies,

fruits, eggs, cheese, fish, meats, sweet potatoes, nuts, rice, etc.

These choices should allow for settling into a sensible and healthy

ratio without knowing exactly what it is. It’s not as if a hawk ever

flies up into the air with the aim to “bump up the fats in my

macronutrient ratio.” With some nudging in the right direction, it

should come naturally.

The MR is the breakdown of the percentage of calories taken up

in the food by each nutrient, as in 30 percent carbs, 50 percent fats,

and 20 percent protein. As the lingo goes, this would be a 30-50-20

ratio. Various essential micronutrients, such as vitamins and

minerals, are in there too (hopefully!), but they are tiny by weight

compared with the macros .

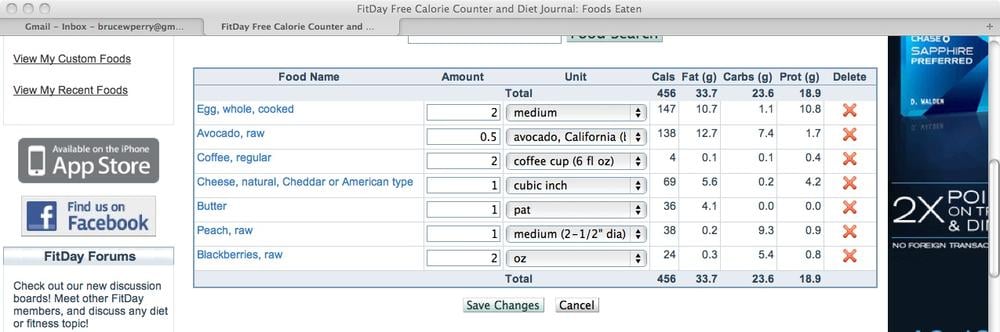

Figure 1

shows a FitDay (www.fitday.com)

breakdown of what I had for breakfast this morning, about 460 calories

worth of fried eggs, fruit, and cheese. Each of the fat grams is worth

about 9 calories, while carbs and protein add up to about 4 calories

each.

Note

The term kcal or “kilogram calorie” is a more

precise term in nutrition than “calorie.” It means the amount of

energy required to raise the temperature of a kilogram of water 1

degree Celsius. “kcal,” however, has the same meaning as “calorie”

in the context of this discussion.

Figure 1. Eggs, fruit, and cheese for breakfast

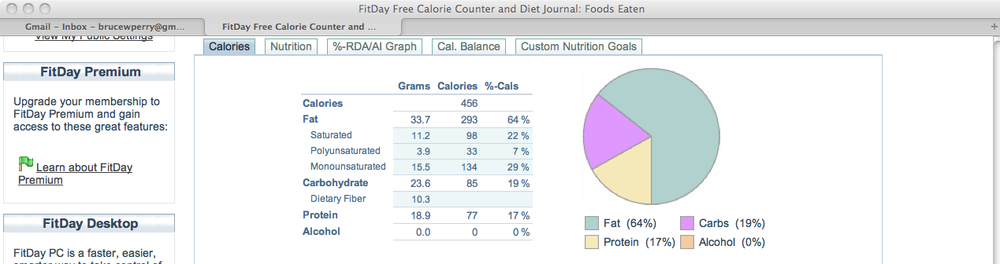

The MR for this small meal was 19 percent carbs, 64

percent fat, and 17 percent protein, as shown in Figure 2. The shorthand

way to describe this ratio is 19-64-17. A macronutrient ratio is

generally one piece of data out of a big nutrition picture. If you

really wanted to analyze your nutrition inputs, you would be better

off calculating the MR for a typical week of eating, along with your

calorie intake (i.e., 2,400 calories per day) and perhaps your

activity levels, to put all the data into a proper context.

Figure 2. The macronutrient ratio for a small meal, displayed on

FitDay

In this small 460-calorie meal, the ratio of fats was much

higher than carbs, even though I ate less than 10 more fat grams,

because fats have more than twice the calorie or energy content of

carbs. They are thus considered energy-dense

foods. The wine, beer, or other alcohol you might drink (actually

containing the chemical ethanol) has about 7 calories per gram.

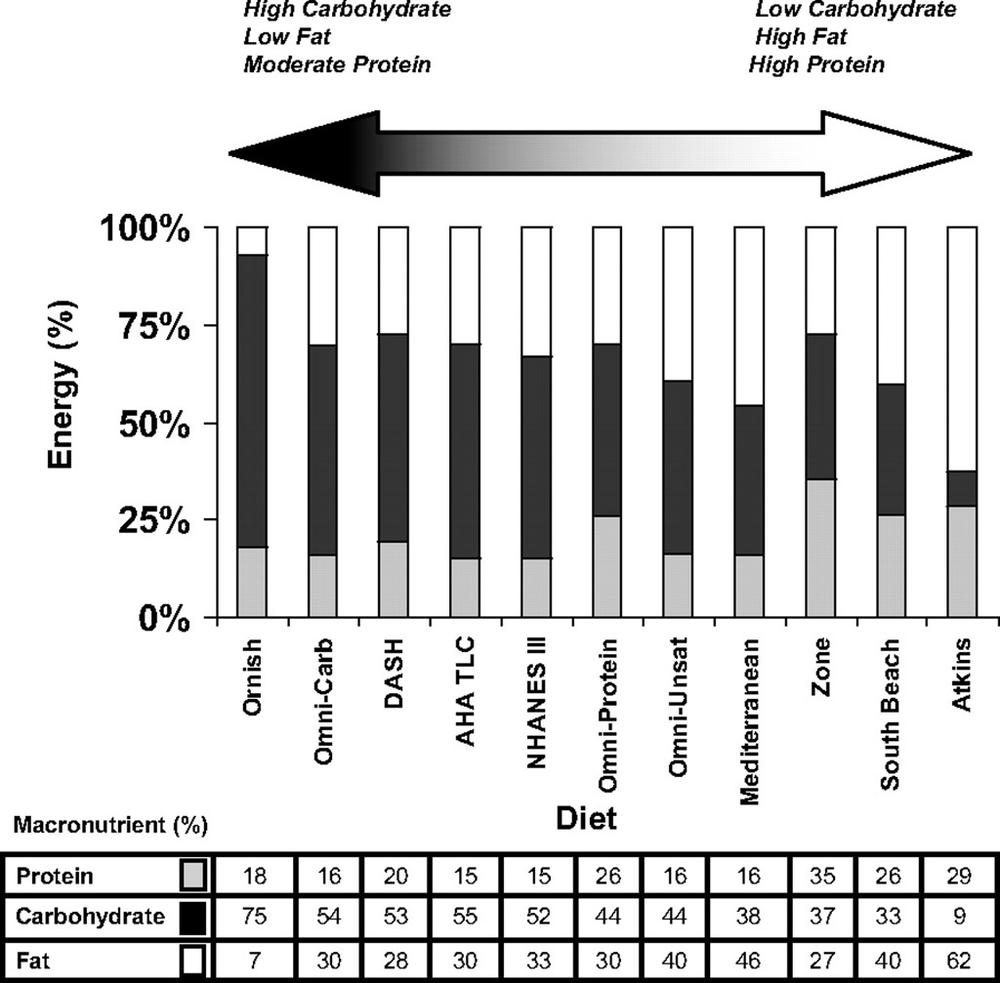

As you may already know, recommendations for an ideal

macronutrient ratio range all over the map. Figure 3 shows the MRs

for a number of popular diets, including the Mediterranean, Zone,

DASH, South Beach, Atkins, and Ornish eating plans. They range from

high-carb diets (e.g., Ornish) to low-carb, higher protein plans,

which is often another way of saying high-fat diets, because the

majority of calories are obtained from fat (e.g., Atkins). Figure 3 is derived from

a 2008 article in the American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition called “Alternatives for macronutrient intake and

chronic disease.”

The featured eating plans differ wildly from each other; just

look at Ornish (75 carbs-7 fat-8 protein) compared with Mediterranean

(46 carbs-38 fat-16 protein). Each specially designed diet seems to

spawn another one. I’ve often wondered why no one has invented the

“Symmetrical Diet” or “Perfect Synchronicity” involving an exact

partition of calories for all three macronutrients: 33-33-33. Not

catchy enough? Or maybe I just haven’t looked hard enough; it must be

out there.

Figure 3. The macronutrient ratios for several popular diets

(www.ajcn.org/content/88/1/1.full.pdf+html

If the numbers begin looking more and more like the offerings of

a roulette wheel, then maybe constantly pondering and switching

between them is equivalently meaningful to playing casino games with

your food. Meanwhile, the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of

Medicine, a US public health authority, has produced its own

guidelines involving MRs. They are called Acceptable Macronutrient

Distribution Ranges (AMDRs).

Note

These are ranges of percentages that the Food and

Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine recommends for each

macronutrient, as follows: carbs, 45 to 65 percent for all age groups;

fat, 20 to 35 percent depending on age; and protein, 10 to 35 percent.

These numbers leave room for all kinds of diets, including ones

dominated by carbs (65 percent), even though the accompanying comments

point out that “the higher range” of carb intake leaves you open to

high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol.

For example, based on these recommendations, you could have a

diet that is 65 percent carbs-20 percent fat-15 percent protein, or

one that goes in a dramatically different direction: 45 carbs-30

fat-25 protein. In other words, there’s a lot of wiggle room within

the conventional wisdom.