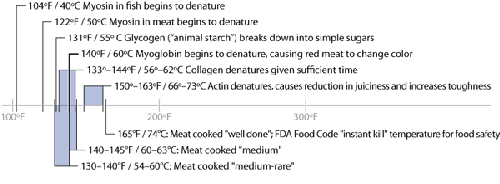

1. 104°F / 40°C and 122°F / 50°C: Proteins in Fish and Meat Begin to Denature

Chances are, you haven’t given much thought to the chemical reactions that happen to a

piece of meat when the animal supplying it is slaughtered. The primary change is, to put

it bluntly, that the animal is dead, meaning the circulatory system is no longer supplying

the muscle tissue with glycogen from the liver or oxygen-carrying blood. Without oxygen,

the cells in the muscle die, and preexisting glycogen in the muscle tissue dissipates,

causing the thick and thin myofilaments in the muscle to fire off and bind together

(resulting in the state called rigor mortis).

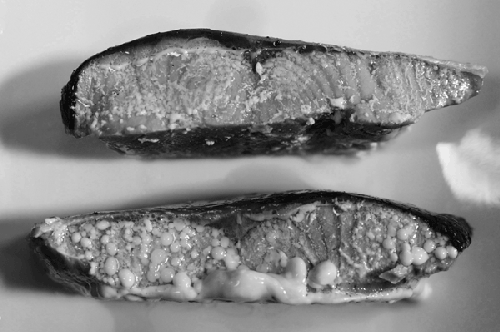

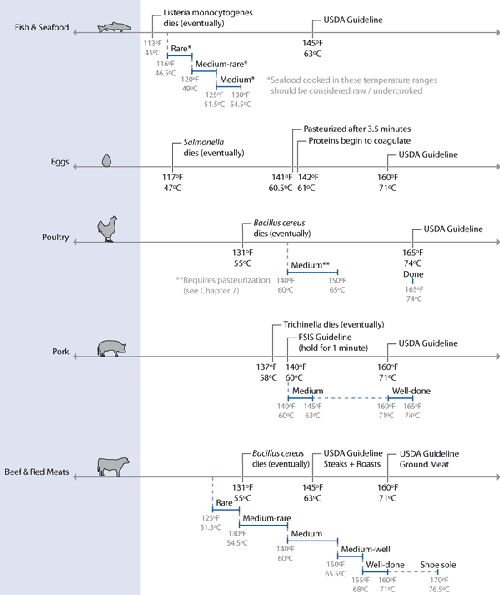

Denaturation temperatures of various types of proteins (top portion) and

standard doneness levels (bottom portion).

Somewhere around 8

to 24 hours later, the glycogen supply is exhausted and enzymes naturally present in the

meat begin to break down the bonds created during rigor mortis (postmortem

proteolysis). Butchering before this process has run its course will affect

the texture of the meat. Sensory panels have found that chicken breasts cut off the

carcass before rigor mortis was over have a tougher texture than meat left on the bone

longer. And since time is money, much mass-produced meat is slaughtered and then butchered

straightaway. (I knew there was a reason why roasted whole birds

taste better!)

Proteins in meat can be divided into three general categories: myofibrillar proteins

(found in muscle tissue, these enable muscles to contract), stromal proteins (connective

tissue, including tendons, that provide structure), and sarcoplasmic proteins (e.g.,

blood).

Muscle tissue is primarily composed of only a few types of proteins, with myosin and

actin being the two most important types in cooking. About two-thirds of the proteins in

mammals are myofibrillar proteins. The amount of actin and myosin differs by animal type

and region. Fish, for example, are made up of roughly twice as much of these proteins as

mammals.

Lean meat is mostly water (65–80%), protein (16–22%), and fat (1.5–13%), with sugars

such as glycogen (0.5–1.3%) and minerals (1%) contributing only a minor amount of the

mass. When it comes to cooking a piece of fish or meat, the key to success is to

understand how to manipulate the proteins and fats. Although fats can be a significant

portion of the mass, they are relatively easy to manage, because they don’t provide

toughness. This leaves proteins as the key variable in cooking meats.

Of the proteins present in meat, myosin and actin are the most important from a

culinary texture perspective. If you take only one thing away from this section, let it be

this: denatured myosin = yummy; denatured actin = yucky. Dry, overcooked meats aren’t

tough because of lack of water inside the meat; they’re tough because on a microscopic

level, the actin proteins have denatured and squeezed out liquid in the muscle fibers.

Myosin in fish begins to noticeably denature at temperatures as low as 104°F / 40°C; actin

denatures at around 140°F / 60°C. In land animals, which have to survive warmer

environments and heat waves, myosin denatures in the range of 122–140°F / 50–60°C

(depending on exposure time, pH, etc.) while actin denatures at around 150–163°F /

66–73°C.

Food scientists have

determined through empirical research (“total chewing work” and “total texture preference”

being my favorite terms) that the optimal texture of cooked meats occurs when they are

cooked to 140–153°F / 60–67°C, the range in which myosin and collagen will have denatured

but actin will remain in its native form. In this temperature range, red meat has a

pinkish color and the juices run dark red.

The texture of some cuts of meat can be improved by tenderizing. Marinades and brines

chemically tenderize the flesh, either enzymatically (examples include bromelain, an

enzyme found in pineapple, and zingibain, found in fresh ginger) or as a solvent (some

proteins are soluble in salt solutions). Dry aging steaks works by giving enzymes

naturally present in the meat time to break down the structure of collagen and muscle

fibers. Dry aging will affect texture for at least the first seven days. Dry aging also

changes the flavor of the meat: less aged beef tastes more metallic, more aged tastes

gamier. Which is “better” is a matter of personal taste preference. (Perhaps some of us

are physiologically more sensitive to metallic tastes.) Retail cuts are typically 5 to 7

days old, but some restaurants use meat aged 14 to 21 days.

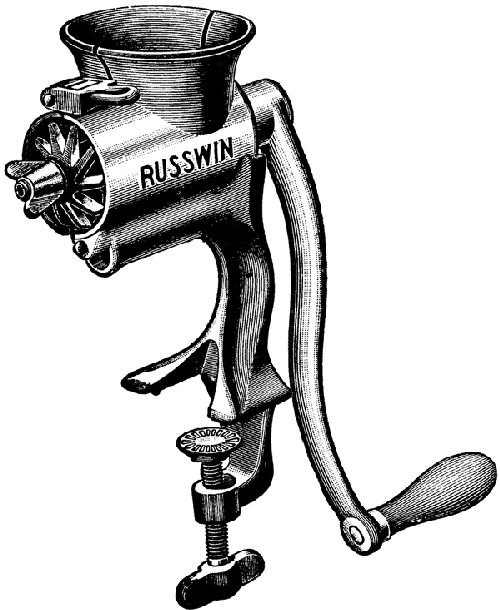

Then there are the mechanical methods for “tenderizing,” which aren’t actually so much

tenderizing as they are masking toughness: for example, slicing muscle fibers against the

grain thinly, as is done with beef carpaccio and London broil, or literally grinding the

meat, as is done for hamburger meat. (Some industrial meat processors “tenderize” meat by

microscopically slicing it using very thin needles, a method called jacquarding.) Applying

heat to meats “tenderizes” them by physically altering the proteins on the microscopic

scale: as the proteins denature, they loosen up and uncurl. In addition to denaturing,

upon uncurling, newly exposed regions of one protein can come into contact with regions of

another protein and form a bond, allowing them to link to each other. This process is

called coagulation, and while it typically occurs in cooking that

involves protein denaturation, it is a separate phenomenon.

Temperatures required for various levels

of doneness. Note that seafood cooked very rare or medium rare and chicken cooked

medium must be held for a sufficiently long period of time at the stated temperature

in order to be properly pasteurized.

Seared Tuna with Cumin and Salt

Pan

searing is one of those truly simple cooking methods that produces a fantastic flavor

and also happens to take care of bacterial surface contamination in the process. The

key to getting a rich brown crust is to use a cast iron pan, which has a higher

thermal mass than almost any other kind of pan. When you drop the tuna onto the pan, the

outside will sear and cook quickly while leaving as much of the center as possible in

its raw state.

You’ll need 3–4 oz (75–100 grams) of raw tuna per person. Slice the tuna into

roughly equal-sized portions, since you’ll be cooking them one or two at a time.

On a flat plate, measure out 1 tablespoon cumin seed and ½ teaspoon (2g) salt

(preferably a flaky salt such as Malden sea salt) per piece of

tuna. On a second plate, pour a few tablespoons of a high-heat-stable oil,

such as refined canola, sunflower, or safflower oil.

Place a cast iron pan on a burner set as hot as possible. Wait for the pan to heat

up thoroughly, until it just begins to smoke.

For each serving of tuna, dredge all sides in the cumin/salt mix, and then briefly

dip all sides in the oil to give the fish a thin coating.

Sear all sides of the fish. Flip to a new side once the current facedown side’s

cumin seeds begin to brown and toast, about 30 to 45 seconds per side.

Slice into ⅓″ (1 cm) slices and serve as part of a salad (place fish on top of mixed

greens) or main dish (try serving with rice, risotto, or Japanese udon noodles).

Notes

-

Keep in mind that the temperature of the pan will fall once you drop

the tuna in it, so don’t use a piece of fish too large for your pan. If you’re

unsure, cook the fish in batches. -

Use coarse sea salt, not rock (kosher) salt or the table salt you’d

find in a salt shaker. The coarse sea salt has a large, flaky grain that prevents

all of the salt from touching the flesh and dissolving.

Coat all sides of the tuna in cumin seeds and salt by pressing the

tuna down onto a plate that has the spice mixture evenly spread out on

it.

Make sure the pan is really hot. Some smoke coming off the fish as it

sears is okay!

Pan-seared tuna will be well-done on the outside and have a very large

“bull’s eye” where the center is entirely raw.