So you’ve picked out a recipe to start

with and you’re raring to go. Now what? Beyond the grocery shopping list, there are a few

things you can do before putting the knife to the cutting board to avoid mishaps while

cooking.

1. Calibrating Your Instruments

A scientist can only run experiments and make observations up to the level of accuracy

that his equipment allows. This isn’t to say that you need to approach the kitchen with

the same rigor that a scientist shows at the lab bench, but if you’re trying to bake

cookies or roast a chicken and your oven is off by 50°F / 28°C, your results will be less

than desirable. The largest variance in most kitchen equipment is usually the oven, and it

can be hard to tell if your oven is running cold or hot just by feel. (Dull knives are

also a common misdemeanor; more on that later.) Check and calibrate your oven using an

oven thermometer. On the road visiting someone and don’t trust their oven? See The Two Things You Should Do to Your Oven RIGHT NOW, below, for instructions on

calibrating an oven using sugar.

2. Prepping Ingredients

When making a meal, start by prepping your ingredients before you begin the cooking

process. Read through the entire recipe, and get out everything you need so you don’t have

to go hunting in the cupboards or the fridge halfway through. Making stir-fry? Slice the

vegetables into a bowl and set it aside before you start cooking. In some cases, you can

do the prep work well in advance of when you start cooking the meal. Restaurants wash,

cut, and store ingredients hours or even days ahead of when they’re needed. The stages of

prepping and cooking are like the stages of compiling and executing in software

programming. If compiling is looking through all the steps and assembling the instructions

into a single stream of optimized commands that are ready to be executed, the prep stage

of cooking is similarly “precomputing” as much of the work as possible so that, when it’s

time to fire off the recipe, you can execute it as quickly and easily as possible.

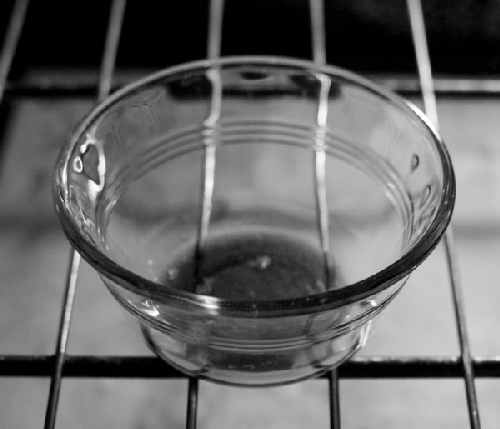

The mise en place technique (French for “put in place”) involves

laying out all the ingredients and utensils needed to cook a dish before starting. Think

of it like cache priming in computer programming: mise en place is equivalent to

prefetching the various bits you’ll need while executing to avoid cache misses. If

you are going to prepare the same dish multiple times (say, omelets for a large brunch),

having a bunch of containers ready with the various fillings in them will allow you to

work quickly. Mise en place isn’t an absolute necessity, although it

does generally make the cooking process smoother. Measure out the ingredients at this

stage whenever possible; this way you’ll have a chance to discover if you’re short of a

critical ingredient (or if it’s gone bad!) before committing to the cooking process. It

also helps avoid those panicked moments of trying to locate a strainer that’s wandered off

while a sauce that needs immediate straining cools down. (Happens to me all the time…)

Sure, a “just-in-time” approach is fine for simple meals. However, if you’re cooking for a

large number of people or attempting a particularly complicated menu, keep the mise en

place approach in mind.