4. Cooking with (a Lot of) Heat

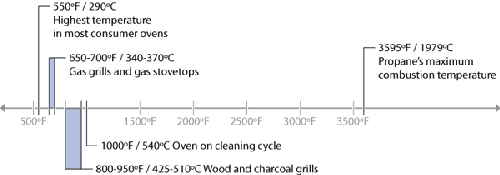

Common and

uncommon hot temperatures.

If cooking at 400°F / 200°C produces something yummy, surely cooking at 800°F / 425°C

must produce something twice as yummy.

But there are some edge cases—just as with “cooking” with cold—where extremely high

heat can be used to achieve certain effects that are otherwise difficult. Let’s take a

look at a few dishes that can be made by transferring lots of heat

using blowtorches and high-temperature ovens.

4.1. Blowtorches for crème brûlée

Blowtorches can be used to provide very localized heat, enabling you to scorch and

burn just those parts of the food at which you aim the flame. Torching tuna sushi,

roasting peppers, and browning sous vide–cooked meats are all common uses, but creating

the sugary crust on crème brûlée is the canonical excuse for a blowtorch in the kitchen.

You can also use a blowtorch to prerender the fatty side of meats—try scoring and then

torching the fatty side until it begins to brown before roasting.

When it comes to buying a torch, skip the “gourmet” torches and head to a hardware

store to pick up a propane blowtorch—not a MAPP gas one, though. The smaller torches

sold by kitchen specialty shops burn butane and work okay, but they don’t pack the same

thermal punch as the hardware-store variety, which have larger nozzles and thus larger

flames.

You can “upgrade” Bananas Foster—a

simple and tasty dessert where the bananas are cooked in butter and sugar, spiked

with rum, and then served over vanilla ice cream—by sprinkling sugar on the cooked

bananas and then using a blowtorch to caramelize the sugar. To create a work

surface, flip a cast iron pan upside-down, line it with foil, and set the bananas

on that.

Practice using a blowtorch by melting sugar sprinkled on a sheet of aluminum foil on

top of a metal cookie sheet or cast iron pan. Don’t get the flame too close; this is the

most common mistake when cooking with a blowtorch. The blue part of the flame is

hottest, but the surrounding air beyond the tip will still be plenty hot. You’ll know

you’re definitely too close when the aluminum foil begins to melt—around 1220°F /

660°C.