2. Smell (Olfactory Sense)

While the sensation of taste is limited to a few basic (and important) sensations,

smell is a cornucopia of data. We’re wired to detect somewhere around 1,000 distinct

compounds and are able to discern somewhere over 10,000 odors. Like taste, our sense of

smell (olfaction) is based on sensory cells

(chemoreceptors) being “turned on” by chemical compounds. In smell,

these compounds are called odorants.

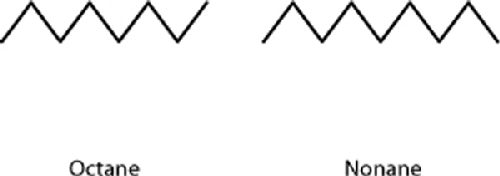

In the case of olfaction, the receptor cells are located in the olfactory epithelium

in the nasal cavity and respond to volatile chemicals—that is, compounds that evaporate

and can be suspended in air such that they pass through the nasal cavity where the

chemoreceptors have a chance to detect them. Our sense of smell is much more acute than

our sense of taste; for some compounds, our nose can detect odorants on the order of one

part per trillion.

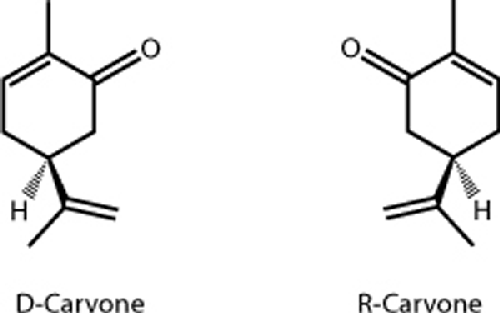

There are a few different theories as to how the chemoreceptors responsible for

detecting smell work, from the appealingly simple (“the receptors feel out the shape of

the odor molecule”) to more complex chemical models. The more recent models suggest that

an odorant can bind to a number of different types of chemoreceptors and a chemoreceptor

can accept a number of different types of odorants. That is, any given odor triggers a

number of different receptors, and your brain applies something akin to a fuzzy

pattern-matching algorithm to recall the closest prior memory. Regardless of the details,

the common theme of the various models suggests that we smell based on some set of

attributes such as the shape, size, and configuration of the odor molecules.

This

more complex model—in which a single odorant needs to be picked up by multiple

receptors—also suggests an explanation for why some items smell odd when you receive only

a weak, partial whiff. To use a music analogy, it’s like not hearing the entire set of

notes that make up a chord: our brains can’t correctly match the sensation and might find

a different prior memory closer to the partial “chord” and misidentify the smell.

Note:

It also appears that we smell in stereo: just as our ears hear separately, we use

our left and right nostrils independently. Researchers at UC Berkeley have found that

with one nostril plugged up, we have a much harder time tracking scents, due to lack of

“inter-nostril communication.”

While you might think of smell as being only what you sense when leaning forward and

using your nose to take a whiff of a rose, that’s only half the picture. Odors also travel

from food in your mouth into the nasal cavity through the shared airway passage: you’re

smelling the food that you’re “tasting.”

When cooking, keep in mind that you can smell only volatile compounds in a dish. You

can make nonvolatile compounds volatile by adding alcohol (e.g., wine in sauces), which

raises the vapor pressure and lowers the surface tension of the compounds, making it that

much more likely that they will evaporate and pass by your chemoreceptors.

Note:

Chemists call this cosolvency. In this case, the ethanol

molecule takes the place of the water molecules normally attached to the compounds,

resulting in a lighter molecule, which then has a higher chance of evaporating.

Temperature also plays an important role in olfaction. We have a harder time smelling

cold foods because temperature partially determines a substance’s volatility.

Your sense of taste is affected by temperature, too. Researchers have found that the

intensity of primary tastes varies with the temperature both of the food itself and of the

tongue. The ideal temperature is 95°F / 35°C, the approximate temperature of the top of

the tongue. Colder foods result in tastes having lower perceived strength, especially for

sugars. It’s been suggested that red wines are best served at room temperature to help

convey their odors, while white wines are better served chilled

to moderate the levels of volatile compounds and sweetness. This would make sense—by

chilling white wine, it’ll be less likely to overpower the milder meals that they

customarily accompany, such as fish.

Then there’s the effect of the temperature of the tongue itself. For example, when

drinking a cold soda, as you consume more and more of it, your tongue will begin to cool

down. And as your tongue cools, you should perceive the soda as being less sweet. There’s

a reason why warm soda is gross: it tastes sweeter, cloyingly so, than when it’s cold.

What does all this mean when you’re in the kitchen? Keep the impact of temperature on your

senses of smell and taste in mind when making dishes that will be served cold. You’ll find

the frozen versions of things like ice cream and sorbet to be weaker tasting and smelling

than their warmer, liquid versions, so adjust the mixtures accordingly.

As an example, try making the following pear sorbet. Note the difference in sweetness

between the warm liquid and the final sorbet. Yes, you could just buy a container of

sorbet and let some of it melt, but where’s the fun in that?