4. Alcohol

A number

of organic compounds that provide aromas in food are readily dissolved in ethanol but not

in water. You will invariably encounter dishes where alcohol is used for its chemical

properties, either as a medium to carry flavors or as a tool for making flavors in the

food available in sufficient quantity for your olfactory system to notice.

Note:

Ethanol can react with carboxylic acids in acid-catalyzed conditions, forming

compounds that then react with more ethanol to generate water and the ester compounds

that help carry aromas up into the nasal cavity.

Alcohol is often added to sauces or stews to aid in releasing aromatic compounds

“locked up” in the ingredients. Try adding red wine to a tomato sauce or dribbling a bit

of Pernod (anise liqueur) on top of a piece of pan-seared cod served with roasted fennel

and rice.

You can also make your own flavor-infused vodkas by adding diced fruit, berries,

herbs, or other spices to straight vodka. And since your concoction doesn’t have to be

shelf-stable like commercial varieties, you can generate better-tasting infusions. Don’t

limit yourself to just vodkas, either; try adding mint and a small quantity of sugar syrup

to bourbon whiskey and storing it in the freezer.

Fat-Washing Alcohols: Butter-Infused Rum, Bacon-Infused BourbonThe term “fat washing” Why do this? Because you can create infused alcohols with flavors that Create an infusion of 3–5% fat and 95–97% alcohol. Try 2 teaspoons (10g) of melted Try using an immersion blender to kick-start the infusion. After infusing, place infusion in freezer until fats have solidified, and then

Notes

|

Vanilla ExtractIn a small glass jar with a tight-fitting

Screw lid on jar or place plastic wrap over top and store in a cool, dark place Notes

|

Sage Rush: Gin, Sage, and Grapefruit JuiceThis is a simple cocktail and a darn good one. And having a simple, Put two or three sage leaves (fresh!) in a shaker and muddle with the back side of a Note |

When a Molecule Meets a Molecule…

Alcohol

isn’t the only solvent in the kitchen. The same chemical interactions that give alcohol

its magic apply to oil and water, which is why recipes call for steps such as toasting

caraway seeds in oil: the oil captures the molecules responsible for the characteristic

nutty flavors developed and released by heating the seeds.

But how does a solvent work? What happens when one molecule

bumps into another molecule? Will they form a bond (called an intermolecular

bond) or repel each other? It depends on a number of forces that stem from

differences in the electrical charges and charge distributions of the two

molecules.

Of the four types of bonds defined in chemistry, two are of culinary interest: polar

and nonpolar.

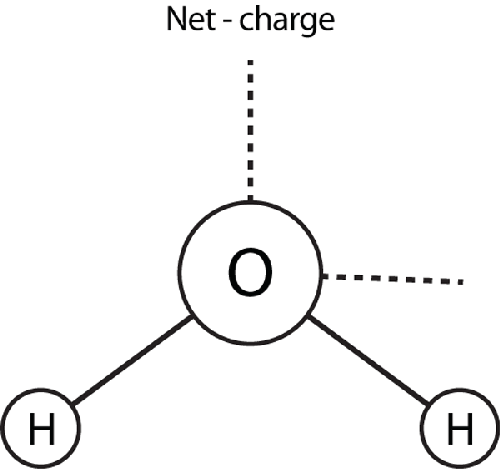

A molecule that has an uneven electrical field around it or that has an uneven

arrangement of electrons is polar. The simplest arrangement, where

two sides of a molecule have opposite electrical charges, is called a

dipole. Water is polar because the two hydrogen atoms attach

themselves to the oxygen atom such that the molecule as a whole has a negatively charged

side. When two polar molecules bump into each other, a strong bond forms between the

first molecule’s positive side and the second molecule’s negative side, just like when

two magnets are lined up. On the atomic level, the side of the first molecule that has a

negative charge is balancing out the side of the second molecule that has a positive

charge.

A water molecule is polar because the electrostatic field around the

molecule is asymmetric, due to the oxygen atom being more electronegative than the

hydrogen atoms and the resulting differences in how the two hydrogen atoms share

their electrons with the oxygen atom. (Electron sharing is another type of bond, a

covalent bond.)

A molecule that has a spherically symmetric electrostatic field—that is, there is no

dipole, and the molecule doesn’t have a “side” that has a different electrical charge—is

nonpolar. Oil is nonpolar because of the shape in which the

carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen atoms arrange themselves.

In most cases, when a polar molecule bumps into a nonpolar molecule, the polar

molecule is unlikely to find an electron to balance out its electrical field. It’s a bit

like trying to stick a magnet to a piece of wood: the magnet and wood aren’t actively

repelled by each other, but they’re also not actually attracted. It’s the same for

polar-nonpolar interaction: the molecules might bounce into each other, but they won’t

stick and will end up drifting off and continuing to bounce around into other

molecules.

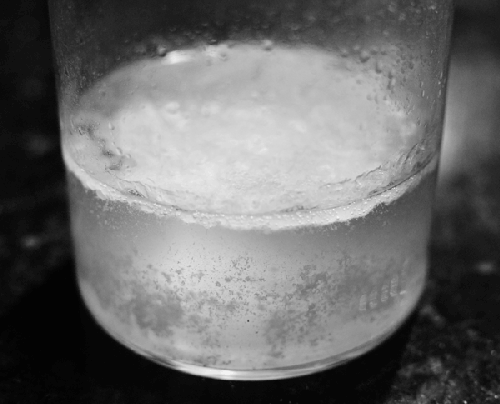

This is why oil and water do not mix. The water molecules are polar and form strong

intermolecular bonds with other polar molecules, which are able to balance out their

electrical charges. At an atomic level, the oil doesn’t provide a sufficiently strong

bonding opportunity for the negatively charged side of the water molecule.

Water and sugar (sucrose), however, get along fine. Sucrose is also polar, so the

electrical fields of the two molecules are able to line up to some degree. The strength

of the intermolecular bond depends on how well the two different compounds line up,

which is why some things dissolve together well while others only dissolve together to a

certain point.